Creating an echo

Art is books, too.

When I became an art teacher, I inherited a curriculum which I loved, and a room full of amazing art supplies. The first order I made was for books.

My father was a secondary school librarian, amongst other things, and I grew up reading my way through the stacks - fiction A-Z, plays, poetry, in it all went, some of it barely hitting the sides, some of it inevitably forming my world view. Even though I almost exclusively read fiction on my Kindle nowadays, I buy art and design books all the time, and use them for ideas much more than the internet.

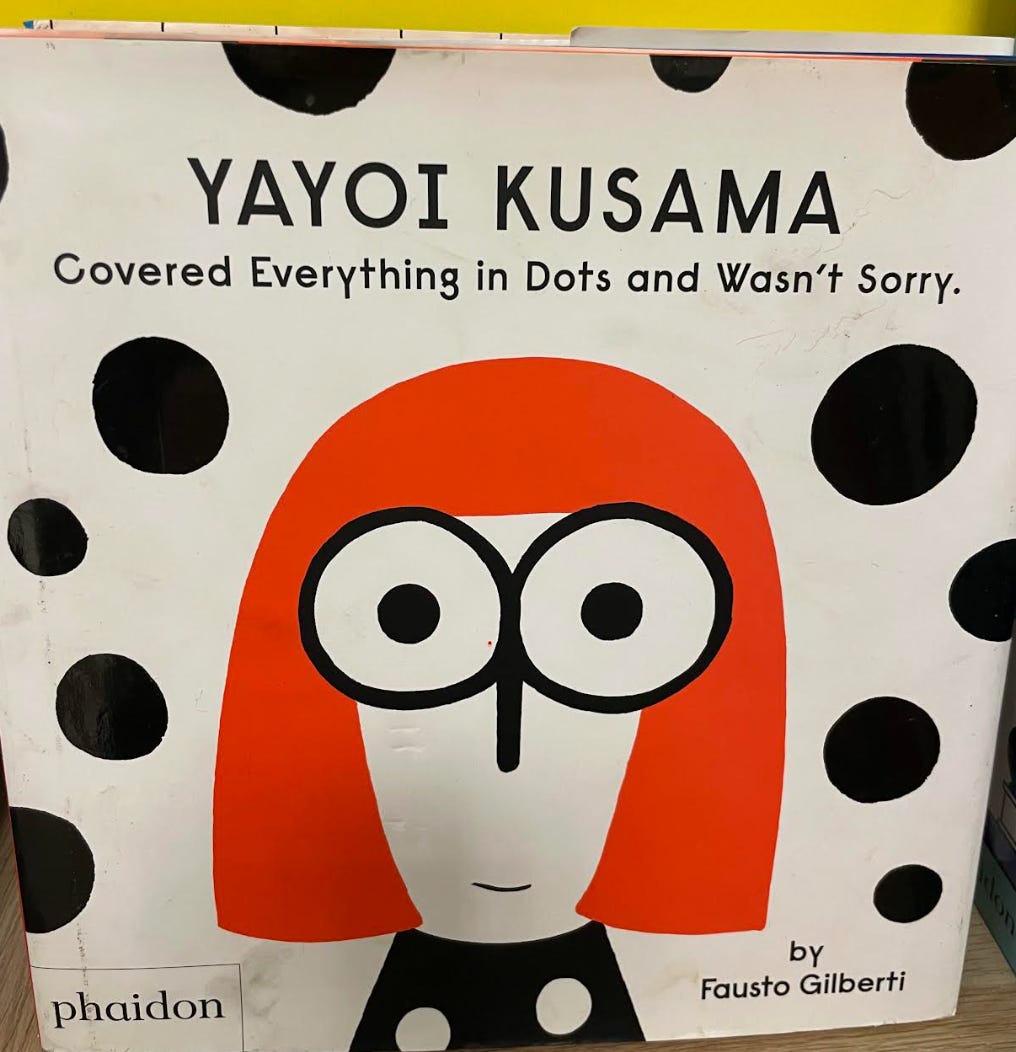

There already were quite a lot of books in the artroom, and I wanted to extend the collection to include more women artists, and artists of colour. The younger (pre-school) children do an amazing, immersive unit on art, discovering Matisse, Klee, Pollock, Kandinsky, Hepworth… I love Matisse! And Klee! And Kandinsky! How great that young kids are encouraged to look at this art! But at the same time, I found myself thinking, “Why is always the same artists? Why is it always dead white men? Where are the women? Oh, OK, they’ve shoehorned Barbara Hepworth in there”. And these artists produced art that is amazingly attractive to children, and there are no shortage of teaching materials about them. But surely we can do better. So in came Sophie Tauber-Arp as a collage unit for me to teach, and Yayoi Kusama across the board.

Creating an echo. Some of these kids will spend their lives exposed to art, dragged around art galleries and museums and every musty church with a fresco on the wall. Others won’t, but at various times in their lives they will hear the name or see the work of an artist, and while they may not remember that they did a project around that artist in second grade, they will be able to remember that they know that artist. Perhaps a child who thinks that art is beyond them because they can’t draw will realise that art is about emotions, not perfection. I hope that all of them will know that creativity comes in many guises, and there are many paths into a love of art. But mainly I am hoping that the echo means that their perception of value in art isn’t limited to the work of dead white men.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the art of dead white men. One of the best exhibitions I ever saw was the Matisse/Diebenkorn one at SFMOMA in 2016? and I am so happy the Seagram Rothkos are back at Tate Modern, so I can sit and soak them up whenever I am in London. But there is already so much out there about these artists, and if we are talking about projects for children, who is more joyous than Alma Thomas, what more fun than Yayoi Kusama’s dots?

And these women make it easy to pull in meaningful themes for young children, because their art is about self-expression, and connection. Not only the women either: this summer I saw Do Ho Suh’s amazing installation at Tate Modern and am basing the Grade 5 sculpture project around his idea of home and memory - especially apt for an international school with a sizeable transient population.

The books below are the ones I use consistently. Sometimes we read a book at the beginning of a lesson (and we might read the same one for a month, in order to fully discuss the ideas), but it is accepted practice in any lesson that if you have finished early, or run out of steam, the choices are to look at a book or draw in your sketchbook. A kindergarten lesson will typically end with the last two kids sitting at the table finishing off, while everyone else has gradually gravitated to sitting on the floor with a book.

Often the book is this one, which is by now so battered that the last feature has actually fallen off, but oops! it happens.

I read this book to every class, Kindergarten to Grade 5. At least twice a week, a student will show me their work, and explain how they Beautiful Oopsed a potential problem. For every student who exclaims when something goes wrong, there will be another who comforts them with the words, “it’s a beautiful oops!” Admittedly, I may have swung the pendulum too far: every so often I hear someone mutter under their breath, “Quick! Where does she keep the erasers?”, and a younger student confidently told me he had gone home and told his parents that all art was a series of mistakes. But this book is instrumental at underlining the importance of risk-taking in art, and I value the heavy lifting it does for me in teaching that.

I have just started using this book as inspiration for a first grade project, for the third year running. Eric Carle’s words and images are so appealing, and so worth poring over. By the time I’ve read it a few times, the kids read it with me: “A BLUE! HORSE! … Aaaaaaaaaaaaannnndddd….” We talk about how many colours are contained in his coloured animals, and why it’s OK to not just depict things as they are. I have read this book too many times to mention, and I still love reading and looking at it.

I bought this book this summer, attracted by the joyous colour of Yinka Ilori, but also by the words, which should be spoken to all aspiring and even reluctant young artists. It’s impossible for the audience not to comment on the amazing illustrations, even as they listen to the words. And it’s a great way to show kids how art is so much more than a realistic depiction of an object.

Oh, Louise! How I love your emotional creations. When the Switch House at Tate Modern first opened, there were a series of rooms dedicated to Louise Bourgeois, and it was the first time I’d got to really experience her work. But this kid’s book gave me a deeper understanding, and it’s been rewarding to use it as a teaching aid. This series of books are absolutely fantastic, but what I love about this one is that putting the spiders front and centre immediately intrigues kids, and the themes of family and connectedness are relatable. I love the reference to how Louise associated spiders with her mother, who worked on tapestries among other things. Last year I did a project with the second grade using this book, culminating in creating a giant cobweb, which we filled up with both pipe cleaner spiders and depictions of family and pets.

This is another book in the series, and Yayoi Kusama is now part of the art curriculum from the babies upwards. Of course, the dots are fun, but this book puts them in context - she drew the dots because they made her feel connected, and that is something any child can understand.

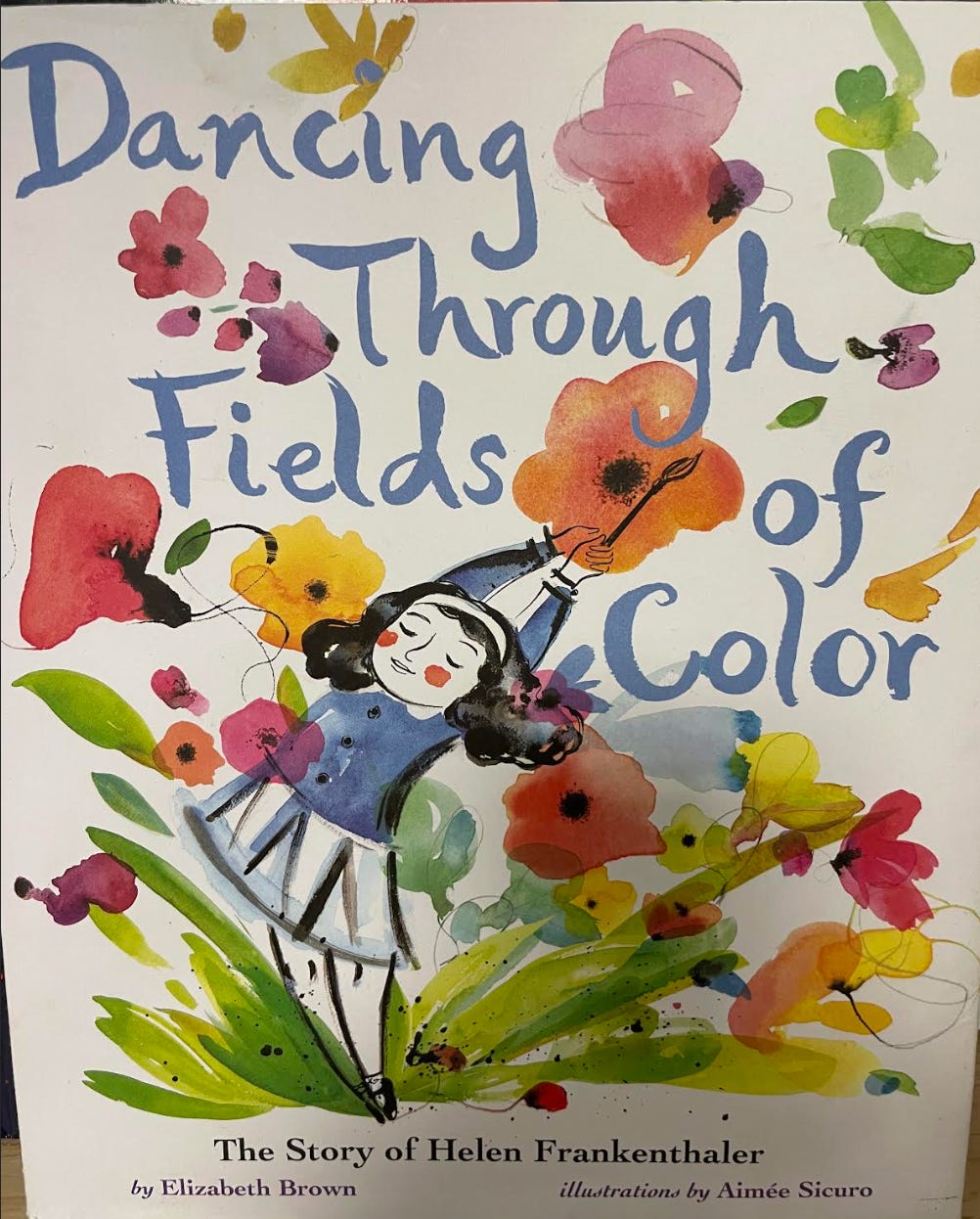

The illustrations in this book are gorgeous: expressive and evocative. This book was a great lead into an exploration of art and creativity as expressions of emotion. Plus it’s just a good book to read as a subtle way to show why there are fewer women artists on the tip of everyone’s tongue, and it wasn’t because they weren’t making great art.

As is this one.

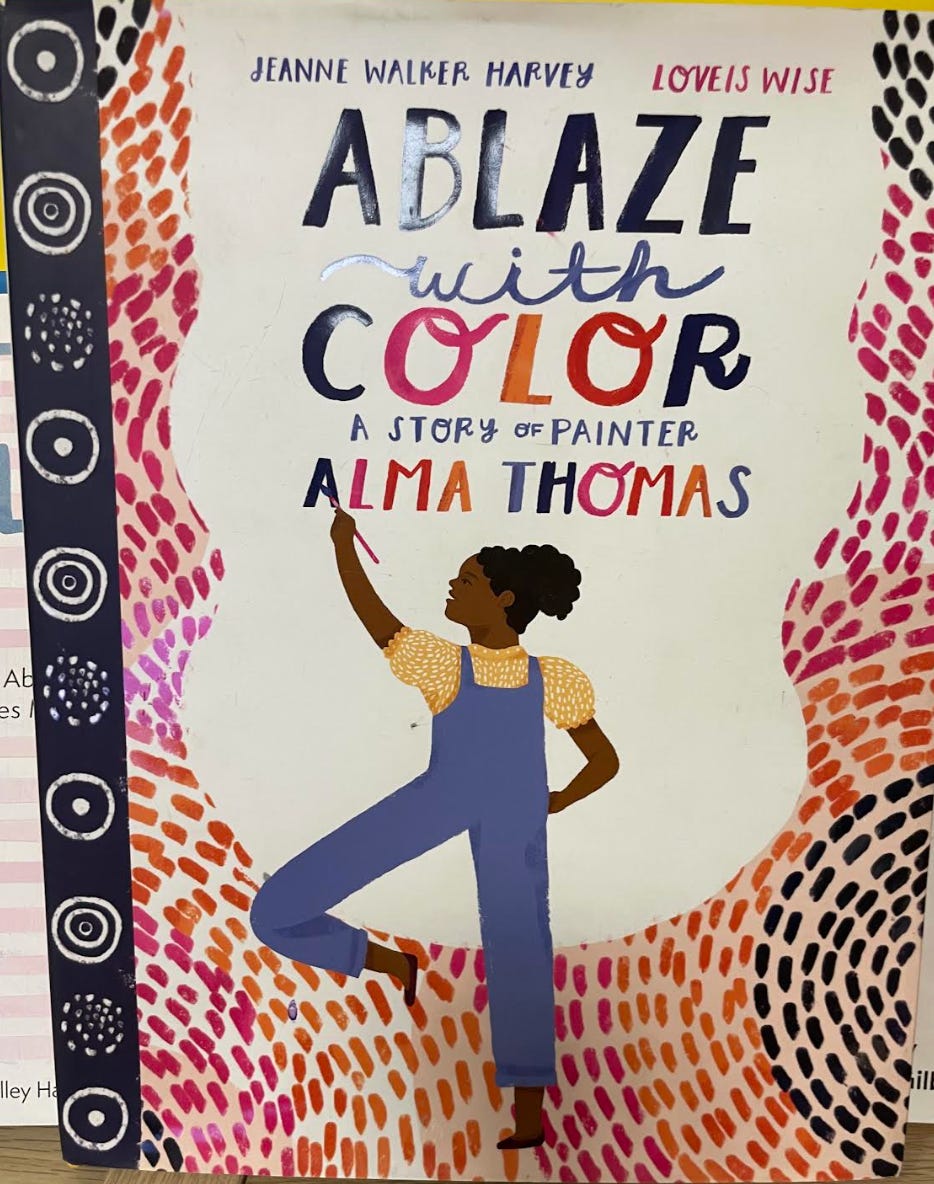

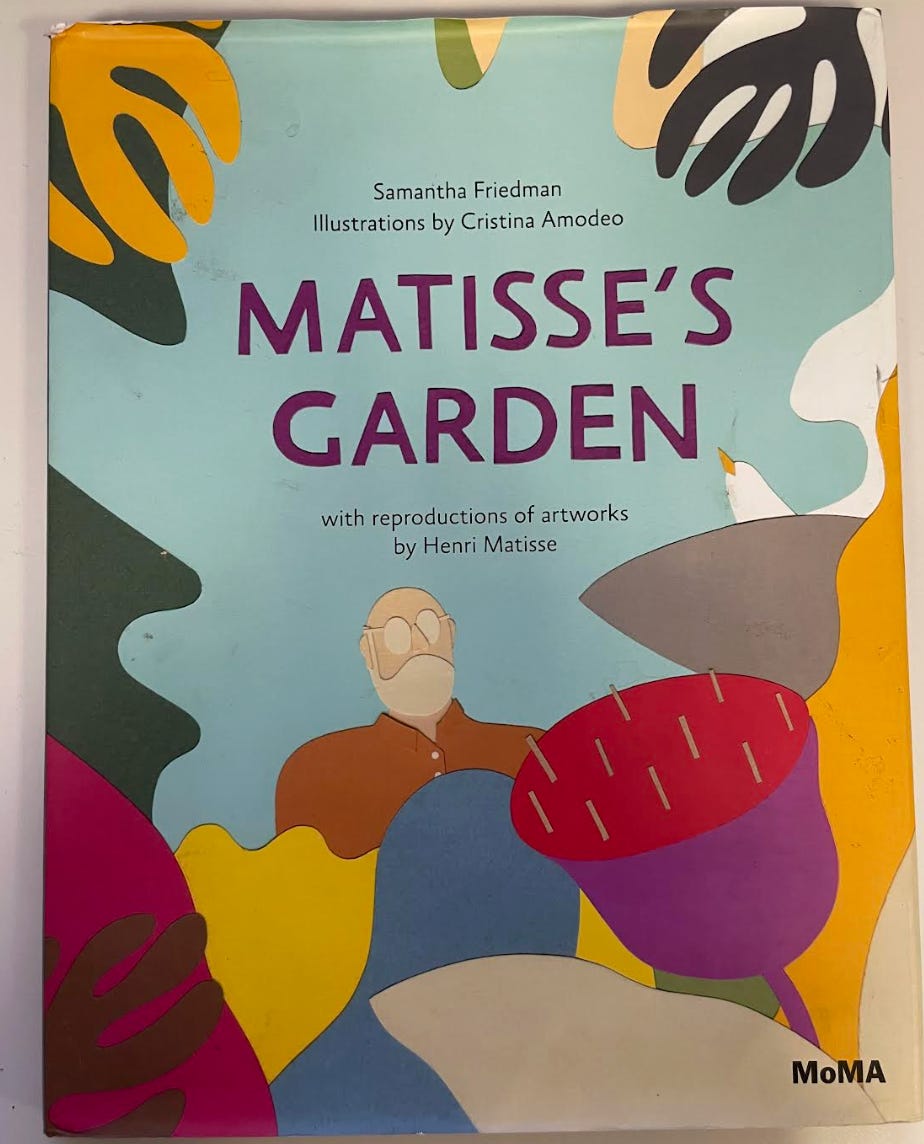

I do mini projects across the grade levels using the work of Alma Thomas as inspiration, but she’s one of the artists I look at with the first graders. Last year, as soon as I showed one class the cover of the book, one little girl exclaimed, “Oh! She looks like me!” The problem with the beloved dead white men, is that I don’t see kids’ faces light up with recognition of representation when I hold up the cover of Matisse’s Garden (although they do light up with excitement at the beauty of the illustrations, and I am absolutely not knocking Matisse, one of my favourite artists). In any case, this book is lovely to read and look at, and it also touches on segregation, which can open up the conversation. A lot of these art books for children are especially powerful because of their emphasis on resilience and creativity as an outlet for emotions.

I love this book so much that I bought it for my ex-librarian art-loving father. It’s a gorgeous book to read with kids, and it’s a nice way to talk about colour theory as well as being an intro to collage projects. I also like that it is yet another reminder that artists will art, whatever their age and state of infirmity.

This book is one we occasionally read at the end of a lesson when everyone cleaned up faster than expected and the teacher is a bit late, and it’s also one certain kids will curl up in my chair with. The illustrations tell the other half of the story, and it’s not a book that needs a lot of teacher interpretation, the kids take from it what they need.

Faith Ringold is an artist I look at with the fifth grade students for their final project, so it’s not one of the books on the pile near my desk. The students are encouraged to look at other books about and by her which we have in our school library, and in art the focus is on her activism and particularly creating art and craft as a meaningful reflection, but of course there are some good conversations to be had around racism and misogyny, as always.

I love how the illustrations in these books add to the words. I love the kids’ reactions to the books when I show them to them, and how they gravitate towards them. I love that they are getting visual inspiration from a book and not an ipad, which makes it easier to encourage them to put their own spin on how they are inspired, rather than them feeling they need to create an exact copy.

I often feel that rather than teaching, my role is much more as a facilitator. Sometimes I bang on at such length about how art is so much more than a realistic drawing, that the students are surprised when I do draw something: “Oh, that’s quite good!” they say in encouraging tones. But I want them to feel that they can find their way in, and that they can make mistakes and try things out, and these books help me to get that across. Hence the book in the image below, which introduces children to the idea of land art, photography, craft, graffiti! all coming under the same umbrella as the more mainstream disciplines.

I lean heavily on the excellent Tate Kids website and I have some favourite videos on there, but I also have several of their art books for kids. I have a whole shelf of beautiful books across one wall of the art room, but these are the ones where you can see the fingerprints, and the cracked spines. These are the books that help to create the echo.

Thank you for reading this far. I’d love to hear recommendations for other art books to read, and if you’d like to share, comment, like or subscribe if you aren’t already, I would be thrilled!

(I haven’t linked because the details are all on the covers, and tracking them down can be quite country specific. If I could I’d order all the books from here or here.)

Oh Louise, this is so fascinating and so beautiful. I hadn’t thought about the impact of art in children’s books in all these ways, but I do know that my daughter’s beloved Madeleine in Paris, Eloise at the Plaza (and others!) and Olivia books, which a friend sent us gifts to her as a little girl, from Canada, had a huge impact on her (AND us!). Even her beloved Maisy board books by Lucy Cousins were so beautifully illustrated, really capturing her imagination – and also Lauren Child’s beautiful version of The Princess and the Pea. But what you write about Yayoi Kusama’s dots, and the connection they symbolise, is so powerful – and I absolutely love that you got to your father the Matisse book. Beyond precious! (As is that photo, top of post! 💖)

They are all very good friends as well, forgot to add Kevin Murray an Australian. Who lives in Rome for past 60 years, like me, we used to teach together Along with Dennis at ORT school and NDI